| United States Armed Forces |

|---|

|

| Executive departments |

| Staff |

| Military departments |

| Military services |

| Command structure |

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States.[12] Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Signal Corps, the USAF was established as a separate branch of the United States Armed Forces in 1947 with the enactment of the National Security Act of 1947. It is the second youngest branch of the United States Armed Forces[lower-alpha 1] and the fourth in order of precedence. The United States Air Force articulates its core missions as air supremacy, global integrated intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, rapid global mobility, global strike, and command and control.

The United States Air Force is a military service branch organized within the Department of the Air Force, one of the three military departments of the Department of Defense. The Air Force through the Department of the Air Force is headed by the civilian Secretary of the Air Force, who reports to the Secretary of Defense and is appointed by the President with Senate confirmation. The highest-ranking military officer in the Air Force is the Chief of Staff of the Air Force, who exercises supervision over Air Force units and serves as one of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. As directed by the Secretary of Defense and Secretary of the Air Force, certain Air Force components are assigned to unified combatant commands. Combatant commanders are delegated operational authority of the forces assigned to them, while the Secretary of the Air Force and the Chief of Staff of the Air Force retain administrative authority over their members.

Along with conducting independent air operations, the United States Air Force provides air support for land and naval forces and aids in the recovery of troops in the field. As of 2017[update], the service operates more than 5,369 military aircraft[13] and 406 ICBMs.[14] The world's largest air force, it has a $156.3 billion budget[15] and is the second largest service branch of the U.S. Armed Forces, with 329,614 active duty airmen,[16] 172,857 civilian personnel,[17] 69,056 reserve airmen,[18] and 107,414 Air National Guard airmen.[19]

Mission, vision, and functions

Missions

According to the National Security Act of 1947 (61 Stat. 502), which created the USAF:

- In general, the United States Air Force shall include aviation forces both combat and service not otherwise assigned. It shall be organized, trained, and equipped primarily for prompt and sustained offensive and defensive air operations. The Air Force shall be responsible for the preparation of the air forces necessary for the effective prosecution of war except as otherwise assigned and, in accordance with integrated joint mobilization plans, for the expansion of the peacetime components of the Air Force to meet the needs of war.

Section 9062 of Title 10 US Code defines the purpose of the USAF as:[20]

- to preserve the peace and security, and provide for the defense, of the United States, the Territories, Commonwealths, and possessions, and any areas occupied by the United States;

- to support national policy;

- to implement national objectives;

- to overcome any nations responsible for aggressive acts that imperil the peace and security of the United States.

Core missions

The five core missions of the Air Force have not changed dramatically since the Air Force became independent in 1947, but they have evolved and are now articulated as air superiority, global integrated ISR (intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance), rapid global mobility, global strike, and command and control. The purpose of all of these core missions is to provide what the Air Force states as global vigilance, global reach, and global power.[21]

Air superiority

Air superiority is "that degree of dominance in the air battle of one force over another which permits the conduct of operations by the former and its related land, sea, air, and special operations forces at a given time and place without prohibitive interference by the opposing force" (JP 1-02).[22][23][24][25]

Offensive Counter-Air (OCA) is defined as "offensive operations to destroy, disrupt, or neutralize enemy aircraft, missiles, launch platforms, and their supporting structures and systems both before and after launch, but as close to their source as possible" (JP 1-02). OCA is the preferred method of countering air and missile threats since it attempts to defeat the enemy closer to its source and typically enjoys the initiative. OCA comprises attack operations, sweep, escort, and suppression/destruction of enemy air defense.[22]

Defensive Counter-Air (DCA) is defined as "all the defensive measures designed to detect, identify, intercept, and destroy or negate enemy forces attempting to penetrate or attack through friendly airspace" (JP 1-02). In concert with OCA operations, a major goal of DCA operations is to provide an area from which forces can operate, secure from air and missile threats. The DCA mission comprises both active and passive defense measures. Active defense is "the employment of limited offensive action and counterattacks to deny a contested area or position to the enemy" (JP 1-02). It includes both ballistic missile defense and airborne threat defense and encompasses point defense, area defense, and high-value airborne asset defense. Passive defense is "measures taken to reduce the probability of and to minimize the effects of damage caused by hostile action without the intention of taking the initiative" (JP 1-02). It includes detection and warning; chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear defense; camouflage, concealment, and deception; hardening; reconstitution; dispersion; redundancy; and mobility, counter-measures, and stealth.[22]

Airspace control is "a process used to increase operational effectiveness by promoting the safe, efficient, and flexible use of airspace" (JP 1-02). It promotes the safe, efficient, and flexible use of airspace, mitigates the risk of fratricide, enhances both offensive and defensive operations, and permits greater agility of air operations as a whole. It both deconflicts and facilitates the integration of joint air operations.[22]

Global integrated ISR

Global integrated intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) is the synchronization and integration of the planning and operation of sensors, assets, and processing, exploitation, dissemination systems across the globe to conduct current and future operations.[22]

Planning and directing is "the determination of intelligence requirements, development of appropriate intelligence architecture, preparation of a collection plan, and issuance of orders and requests to information collection agencies" (JP 2-01, Joint and National Intelligence Support to Military Operations). These activities enable the synchronization and integration of collection, processing, exploitation, analysis, and dissemination activities/resources to meet information requirements of national and military decision-makers.[22]

Collection is "the acquisition of information and the provision of this information to processing elements" (JP 2-01). It provides the ability to obtain required information to satisfy intelligence needs (via use of sources and methods in all domains). Collection activities span the Range of Military Operations (ROMO).[22]

Processing and exploitation is "the conversion of collected information into forms suitable to the production of intelligence" (JP 2-01). It provides the ability to transform, extract, and make available collected information suitable for further analysis or action across the ROMO.[22]

Analysis and production is "the conversion of processed information into intelligence through the integration, evaluation, analysis, and interpretation of all source data and the preparation of intelligence products in support of known or anticipated user requirements" (JP 2-01). It provides the ability to integrate, evaluate, and interpret information from available sources to create a finished intelligence product for presentation or dissemination to enable increased situational awareness.[22]

Dissemination and integration is "the delivery of intelligence to users in a suitable form and the application of the intelligence to appropriate missions, tasks, and functions" (JP 2-01). It provides the ability to present information and intelligence products across the ROMO enabling understanding of the operational environment to military and national decision-makers.[22]

Rapid global mobility

Rapid global mobility is the timely deployment, employment, sustainment, augmentation, and redeployment of military forces and capabilities across the ROMO. It provides joint military forces the capability to move from place to place while retaining the ability to fulfill their primary mission. Rapid Global Mobility is essential to virtually every military operation, allowing forces to reach foreign or domestic destinations quickly, thus seizing the initiative through speed and surprise.[22]

Airlift is "operations to transport and deliver forces and materiel through the air in support of strategic, operational, or tactical objectives" (Annex 3–17, Air Mobility Operations). The rapid and flexible options afforded by airlift allow military forces and national leaders the ability to respond and operate in a variety of situations and time frames. The global reach capability of airlift provides the ability to apply US power worldwide by delivering forces to crisis locations. It serves as a US presence that demonstrates resolve and compassion in humanitarian crisis.[22]

Air refueling is "the refueling of an aircraft in flight by another aircraft" (JP 1-02). Air refueling extends presence, increases range, and serves as a force multiplier. It allows air assets to more rapidly reach any trouble spot around the world with less dependence on forward staging bases or overflight/landing clearances. Air refueling significantly expands the options available to a commander by increasing the range, payload, persistence, and flexibility of receiver aircraft.[22]

Aeromedical evacuation is "the movement of patients under medical supervision to and between medical treatment facilities by air transportation" (JP 1-02). JP 4-02, Health Service Support, further defines it as "the fixed wing movement of regulated casualties to and between medical treatment facilities, using organic and/or contracted mobility airframes, with aircrew trained explicitly for this mission." Aeromedical evacuation forces can operate as far forward as fixed-wing aircraft are able to conduct airland operations.[22]

Global strike

Global precision attack is the ability to hold at risk or strike rapidly and persistently, with a wide range of munitions, any target and to create swift, decisive, and precise effects across multiple domains.[22]

Strategic attack is defined as "offensive action specifically selected to achieve national strategic objectives. These attacks seek to weaken the adversary's ability or will to engage in conflict, and may achieve strategic objectives without necessarily having to achieve operational objectives as a precondition" (Annex 3–70, Strategic Attack).[22]

Air Interdiction is defined as "air operations conducted to divert, disrupt, delay, or destroy the enemy's military potential before it can be brought to bear effectively against friendly forces, or to otherwise achieve JFC objectives. Air Interdiction is conducted at such distance from friendly forces that detailed integration of each air mission with the fire and movement of friendly forces is not required" (Annex 3-03, Counterland Operations).[22]

Close Air Support is defined as "air action by fixed- and rotary-winged aircraft against hostile targets that are in close proximity to friendly forces and which require detailed integration of each air mission with the fire and movement of those forces" (JP 1-02). This can be as a pre-planned event or on demand from an alert posture (ground or airborne). It can be conducted across the ROMO.[22]

The purpose of nuclear deterrence operations (NDO) is to operate, maintain, and secure nuclear forces to achieve an assured capability to deter an adversary from taking action against vital US interests. In the event deterrence fails, the US should be able to appropriately respond with nuclear options. The sub-elements of this function are:[22]

Assure/Dissuade/Deter is a mission set derived from the Air Force's readiness to carry out the nuclear strike operations mission as well as from specific actions taken to assure allies as a part of extended deterrence. Dissuading others from acquiring or proliferating WMD and delivering them contributes to promoting security and is also an integral part of this mission. Moreover, different deterrence strategies are required to deter various adversaries, whether they are a nation state, or non-state/transnational actor. The Air Force maintains and presents credible deterrent capabilities through successful visible demonstrations and exercises that assure allies, dissuade proliferation, deter potential adversaries from actions that threaten US national security or the populations, and deploy military forces of the US, its allies, and friends.[22]

Nuclear strike is the ability of nuclear forces to rapidly and accurately strike targets which the enemy holds dear in a devastating manner. If a crisis occurs, rapid generation and, if necessary, deployment of nuclear strike capabilities will demonstrate US resolve and may prompt an adversary to alter the course of action deemed threatening to our national interest. Should deterrence fail, the President may authorize a precise, tailored response to terminate the conflict at the lowest possible level and lead to a rapid cessation of hostilities. Post-conflict, regeneration of a credible nuclear deterrent capability will deter further aggression. The Air Force may present a credible force posture in either the Continental United States, within a theater of operations, or both to effectively deter the range of potential adversaries envisioned in the 21st century. This requires the ability to engage targets globally using a variety of methods; therefore, the Air Force should possess the ability to induct, train, assign, educate and exercise individuals and units to rapidly and effectively execute missions that support US NDO objectives. Finally, the Air Force regularly exercises and evaluates all aspects of nuclear operations to ensure high levels of performance.[22]

Nuclear surety ensures the safety, security and effectiveness of nuclear operations. Because of their political and military importance, destructive power, and the potential consequences of an accident or unauthorized act, nuclear weapons and nuclear weapon systems require special consideration and protection against risks and threats inherent in their peacetime and wartime environments. In conjunction with other entities within the Departments of Defense or Energy, the Air Force achieves a high standard of protection through a stringent nuclear surety program. This program applies to materiel, personnel, and procedures that contribute to the safety, security, and control of nuclear weapons, thus assuring no nuclear accidents, incidents, loss, or unauthorized or accidental use (a Broken Arrow incident). The Air Force continues to pursue safe, secure and effective nuclear weapons consistent with operational requirements. Adversaries, allies, and the American people must be highly confident of the Air Force's ability to secure nuclear weapons from accidents, theft, loss, and accidental or unauthorized use. This day-to-day commitment to precise and reliable nuclear operations is the cornerstone of the credibility of the NDO mission. Positive nuclear command, control, communications; effective nuclear weapons security; and robust combat support are essential to the overall NDO function.[22]

Command and control

Command and control is "the exercise of authority and direction by a properly designated commander over assigned and attached forces in the accomplishment of the mission. Command and control functions are performed through an arrangement of personnel, equipment, communications, facilities, and procedures employed by a commander in planning, directing, coordinating, and controlling forces and operations in the accomplishment of the mission" (JP 1-02). This core function includes all of the C2-related capabilities and activities associated with air, cyberspace, nuclear, and agile combat support operations to achieve strategic, operational, and tactical objectives.[22]

At the strategic level command and control, the US determines national or multinational security objectives and guidance, and develops and uses national resources to accomplish these objectives. These national objectives in turn provide the direction for developing overall military objectives, which are used to develop the objectives and strategy for each theater.[22]

At the operational level command and control, campaigns and major operations are planned, conducted, sustained, and assessed to accomplish strategic goals within theaters or areas of operations. These activities imply a broader dimension of time or space than do tactics; they provide the means by which tactical successes are exploited to achieve strategic and operational objectives.[22]

Tactical Level Command and Control is where individual battles and engagements are fought. The tactical level of war deals with how forces are employed, and the specifics of how engagements are conducted and targets attacked. The goal of tactical level C2 is to achieve commander's intent and desired effects by gaining and keeping offensive initiative.[22]

History

The U.S. War Department created the first antecedent of the U.S. Air Force, as a part of the U.S. Army, on 1 August 1907, which through a succession of changes of organization, titles, and missions advanced toward eventual independence 40 years later. In World War II, almost 68,000 U.S. airmen died helping to win the war, with only the infantry suffering more casualties.[26] In practice, the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) was virtually independent of the Army during World War II, and in virtually every way functioned as an independent service branch, but airmen still pressed for formal independence.[27] The National Security Act of 1947 was signed on 26 July 1947, which established the Department of the Air Force, but it was not until 18 September 1947, when the first secretary of the Air Force, W. Stuart Symington, was sworn into office that the Air Force was officially formed as an independent service branch.[28][29]

The act created the National Military Establishment (renamed Department of Defense in 1949), which was composed of three subordinate Military Departments, namely the Department of the Army, the Department of the Navy, and the newly created Department of the Air Force.[30] Prior to 1947, the responsibility for military aviation was shared between the Army Air Forces and its predecessor organizations (for land-based operations), the Navy (for sea-based operations from aircraft carriers and amphibious aircraft), and the Marine Corps (for close air support of Marine Corps operations). The 1940s proved to be important for military aviation in other ways as well. In 1947, Air Force Captain Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier in his X-1 rocket-powered aircraft, beginning a new era of aeronautics in America.[31]

1.) 5/1917–2/1918

2.) 2/1918–8/1919

3.) 8/1919–5/1942

4.) 5/1942–6/1943

5.) 6/1943–9/1943

6.) 9/1943–1/1947

7.) 1/1947–

Antecedents

The predecessor organizations in the Army of today's Air Force are:

- Aeronautical Division, Signal Corps (1 August 1907 – 18 July 1914)

- Aviation Section, Signal Corps (18 July 1914 – 20 May 1918)

- Division of Military Aeronautics (20 May 1918 to 24 May 1918)

- U.S. Army Air Service (24 May 1918 to 2 July 1926)

- U.S. Army Air Corps (2 July 1926 to 20 June 1941)[32] and

- U.S. Army Air Forces (20 June 1941 to 18 September 1947)

21st century

During the early 2000s, two USAF aircraft procurement projects took longer than expected, the KC-X and F-35 programs. As a result, the USAF was setting new records for average aircraft age.[33]

Since 2005, the USAF has placed a strong focus on the improvement of Basic Military Training (BMT) for enlisted personnel. While the intense training has become longer, it also has shifted to include a deployment phase. This deployment phase, now called the BEAST, places the trainees in a simulated combat environment that they may experience once they deploy. While the trainees do tackle the massive obstacle courses along with the BEAST, the other portions include defending and protecting their base of operations, forming a structure of leadership, directing search and recovery, and basic self aid buddy care. During this event, the Military Training Instructors (MTI) act as mentors and opposing forces in a deployment exercise.[34] In November 2022, the USAF announced that it will discontinue BEAST and replace it with another deployment training program called PACER FORGE.[35][36]

In 2007, the USAF undertook a Reduction-in-Force (RIF). Because of budget constraints, the USAF planned to reduce the service's size from 360,000 active duty personnel to 316,000.[37] The size of the active duty force in 2007 was roughly 64% of that of what the USAF was at the end of the first Gulf War in 1991.[38] However, the reduction was ended at approximately 330,000 personnel in 2008 in order to meet the demand signal of combatant commanders and associated mission requirements.[37] These same constraints have seen a sharp reduction in flight hours for crew training since 2005[39] and the Deputy Chief of Staff for Manpower and Personnel directing Airmen's Time Assessments.[40]

On 5 June 2008, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates accepted the resignations of both the Secretary of the Air Force, Michael Wynne, and the Chief of Staff of the Air Force, General T. Michael Moseley. In his decision to fire both men Gates cited "systemic issues associated with... declining Air Force nuclear mission focus and performance".[41] Left unmentioned by Gates was that he had repeatedly clashed with Wynne and Moseley over other important non-nuclear related issues to the service.[41] This followed an investigation into two incidents involving mishandling of nuclear weapons: specifically a nuclear weapons incident aboard a B-52 flight between Minot AFB and Barksdale AFB, and an accidental shipment of nuclear weapons components to Taiwan.[42] To put more emphasis on nuclear assets, the USAF established the nuclear-focused Air Force Global Strike Command on 24 October 2008, which later assumed control of all USAF bomber aircraft.[43]

On 26 June 2009, the USAF released a force structure plan that cut fighter aircraft and shifted resources to better support nuclear, irregular and information warfare.[44] On 23 July 2009, The USAF released their Unmanned Aerial System (UAS) Flight Plan, detailing Air Force UAS plans through 2047.[45] One third of the planes that the USAF planned to buy in the future were to be unmanned.[46] According to Air Force Chief Scientist, Greg Zacharias, the USAF anticipates having hypersonic weapons by the 2020s, hypersonic unmanned aerial vehicles (also known as remotely-piloted vehicles, or RPAs) by the 2030s and recoverable hypersonic RPAs aircraft by the 2040s.[47] Air Force intends to deploy a Sixth-generation jet fighter by the mid–2030s.[47]

Conflicts

The United States Air Force has been involved in many wars, conflicts and operations using military air operations. The USAF possesses the lineage and heritage of its predecessor organizations, which played a pivotal role in U.S. military operations since 1907:

- Mexican Expedition[48] as Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps

- World War I[49] as Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps and United States Army Air Service

- World War II[49] as United States Army Air Forces

- Cold War[50][51][52]

- Korean War[53][54]

- Vietnam War[55][56]

- Operation Eagle Claw (1980 Iranian hostage rescue)[57][58]

- Operation Urgent Fury (1983 US invasion of Grenada)[59][60]

- Operation El Dorado Canyon (1986 US Bombing of Libya)[61]

- Operation Just Cause (1989–1990 US invasion of Panama)[62]

- Gulf War (1990–1991)[63]

- Operation Southern Watch (1992–2003 Iraq no-fly zone)[66]

- Operation Deliberate Force (1995 NATO bombing in Bosnia and Herzegovina)[67]

- Operation Northern Watch (1997–2003 Iraq no-fly zone)[68]

- Operation Desert Fox (1998 bombing of Iraq)[69][70][71]

- Operation Allied Force (1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia)[72]

- Afghanistan War (2001–2021)[73][74][75]

- Operation Enduring Freedom (2001–2014)[76]

- Operation Freedom's Sentinel (2015–2021)[77]

- Iraq War (2003–2011)[78][79]

- Operation Iraqi Freedom (2003–2010)[80]

- Operation New Dawn (2010–2011)[81][82]

- Operation Odyssey Dawn (2011 Libyan no-fly zone)[83][84][85]

- Operation Inherent Resolve (2014–present: intervention against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant)

In addition since the USAF dwarfs all other U.S. and allied air components, it often provides support for allied forces in conflicts to which the United States is otherwise not involved, such as the 2013 French campaign in Mali.[86]

Humanitarian operations

The USAF has also taken part in numerous humanitarian operations. Some of the more major ones include the following:[87]

- Berlin Airlift (Operation Vittles), 1948–1949

- Operation Safe Haven, 1956–1957

- Operations Babylift, New Life, Frequent Wind, and New Arrivals, 1975

- Operation Provide Comfort, 1991

- Operation Sea Angel, 1991[88]

- Operation Provide Hope, 1992–1993[89]

- Operation Provide Promise, 1992–1996[90]

- Operation Unified Assistance, December 2004 – April 2005

- Operation Unified Response, 14 January 2010 – 22 March 2010[91]

- Operation Tomodachi, 12 March 2011 – 1 May 2011[92]

Culture

The culture of the United States Air Force is primarily driven by pilots, at first those piloting bombers (driven originally by the Bomber Mafia), followed by fighters (Fighter Mafia).[93][94][95]

In response to a 2007 United States Air Force nuclear weapons incident, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates accepted in June 2009 the resignations of Secretary of the Air Force Michael Wynne and the Chief of Staff of the Air Force General T. Michael Moseley. Moseley's successor, General Norton A. Schwartz, a former airlift and special operations pilot was the first officer appointed to that position who did not have a background as a fighter or bomber pilot.[96] The Washington Post reported in 2010 that General Schwartz began to dismantle the rigid class system of the USAF, particularly in the officer corps.[97]

In 2014, following morale and testing/cheating scandals in the Air Force's missile launch officer community, Secretary of the Air Force Deborah Lee James admitted that there remained a "systemic problem" in the USAF's management of the nuclear mission.[98]

Daniel L. Magruder Jr. defines USAF culture as a combination of the rigorous application of advanced technology, individualism and progressive airpower theory.[99] Major General Charles J. Dunlap Jr. adds that the U.S. Air Force's culture also includes an egalitarianism bred from officers perceiving themselves as their service's principal "warriors" working with small groups of enlisted airmen either as the service crew or the onboard crew of their aircraft. Air Force officers have never felt they needed the formal social "distance" from their enlisted force that is common in the other U.S. armed services. Although the paradigm is changing, for most of its history, the Air Force, completely unlike its sister services, has been an organization in which mostly its officers fought, not its enlisted force, the latter being primarily a rear echelon support force. When the enlisted force did go into harm's way, such as crew members of multi-crewed aircraft, the close comradeship of shared risk in tight quarters created traditions that shaped a somewhat different kind of officer/enlisted relationship than exists elsewhere in the military.[100]

Cultural and career issues in the U.S. Air Force have been cited as one of the reasons for the shortfall in needed UAV operators.[101] In spite of demand for UAVs or drones to provide round the clock coverage for American troops during the Iraq War,[102] the USAF did not establish a new career field for piloting them until the last year of that war and in 2014 changed its RPA training syllabus again, in the face of large aircraft losses in training,[103] and in response to a GAO report critical of handling of drone programs.[104] Paul Scharre has reported that the cultural divide between the USAF and US Army has kept both services from adopting each other's drone handing innovations.[105]

Many of the U.S. Air Force's formal and informal traditions are an amalgamation of those taken from the Royal Air Force (e.g., dining-ins/mess nights) or the experiences of its predecessor organizations such as the U.S. Army Air Service, U.S. Army Air Corps and the U.S. Army Air Forces. Some of these traditions range from "Friday Name Tags" in flying units to an annual "Mustache Month". The use of "challenge coins" dates back to World War I when a member of one of the aero squadrons bought his entire unit medallions with their emblem,[106] while another cultural tradition unique to the Air Force is the "roof stomp", practiced by Airmen to welcome a new commander or to commemorate another event, such as a retirement.

Organization

Administrative organization

The Department of the Air Force is one of three military departments within the Department of Defense, and is managed by the civilian Secretary of the Air Force, under the authority, direction, and control of the Secretary of Defense. The senior officials in the Office of the Secretary are the Under Secretary of the Air Force, four Assistant Secretaries of the Air Force and the General Counsel, all of whom are appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate. The senior uniformed leadership in the Air Staff is made up of the Chief of Staff of the Air Force and the Vice Chief of Staff of the Air Force.[107]

The directly subordinate commands and units are named Field Operating Agency (FOA), Direct Reporting Unit (DRU), and the currently unused Separate Operating Agency.[108]

The Major Command (MAJCOM) is the superior hierarchical level of command. Including the Air Force Reserve Command, as of 30 September 2006, USAF has ten major commands. The Numbered Air Force (NAF) is a level of command directly under the MAJCOM, followed by Operational Command (now unused), Air Division (also now unused), Wing, Group, Squadron, and Flight.[107][109]

Air Force structure and organization

File:Headquarters US Air Force Badge.png Headquarters, United States Air Force (HQ USAF):

The major components of the U.S. Air Force, as of 28 August 2015, are the following:[113]

- Active duty forces

- 57 flying wings and 55 non-flying wings

- nine flying groups, eight non-flying groups

- 134 flying squadrons

- Air Force Reserve Command

- 35 flying wings

- four flying groups

- 67 flying squadrons

- Air National Guard

- 87 flying wings

- 101 flying squadrons

- 87 flying wings

The USAF, including its Air Reserve Component (e.g., Air Force Reserve + Air National Guard), possesses a total of 302 flying squadrons.[114]

Operational organization

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2018) |

The organizational structure as shown above is responsible for the peacetime organization, equipping, and training of air units for operational missions. When required to support operational missions, the Secretary of Defense (SECDEF) directs the Secretary of the Air Force (SECAF) to execute a Change in Operational Control (CHOP) of these units from their administrative alignment to the operational command of a Regional Combatant commander (CCDR).[115] In the case of AFSPC, AFSOC, PACAF, and USAFE units, forces are normally employed in-place under their existing CCDR. Likewise, AMC forces operating in support roles retain their componency to USTRANSCOM unless chopped to a Regional CCDR.

Air Expeditionary Task Force

"Chopped" units are referred to as forces. The top-level structure of these forces is the Air Expeditionary Task Force (AETF). The AETF is the Air Force presentation of forces to a CCDR for the employment of Air Power. Each CCDR is supported by a standing Component Numbered Air Force (C-NAF) to provide planning and execution of air forces in support of CCDR requirements. Each C-NAF consists of a Commander, Air Force Forces (COMAFFOR) and AFFOR/A-staff, and an Air Operations Center (AOC). As needed to support multiple Joint Force Commanders (JFC) in the CCMD's Area of Responsibility (AOR), the C-NAF may deploy Air Component Coordinate Elements (ACCE) to liaise with the JFC. If the Air Force possesses the preponderance of air forces in a JFC's area of operations, the COMAFFOR will also serve as the Joint Forces Air Component Commander (JFACC).

Commander, Air Force Forces

The Commander, Air Force Forces (COMAFFOR) is the senior USAF officer responsible for the employment of air power in support of JFC objectives. The COMAFFOR has a special staff and an A-Staff to ensure assigned or attached forces are properly organized, equipped, and trained to support the operational mission.

Air Operations Center

The Air Operations Center (AOC) is the JFACC's Command and Control (C2) center. Several AOCs have been established throughout the Air Force worldwide. These centers are responsible for planning and executing air power missions in support of JFC objectives.[116]

Air Expeditionary Wings/Groups/Squadrons

The AETF generates air power to support CCMD objectives from Air Expeditionary Wings (AEW) or Air Expeditionary Groups (AEG). These units are responsible for receiving combat forces from Air Force MAJCOMs, preparing these forces for operational missions, launching and recovering these forces, and eventually returning forces to the MAJCOMs. Theater Air Control Systems control employment of forces during these missions.

Personnel

The classification of any USAF job for officers or enlisted airmen is the Air Force Specialty Code (AFSC).

AFSCs range from officer specialties such as pilot, combat systems officer, special tactics, nuclear and missile operations, intelligence, cyberspace operations, judge advocate general (JAG), medical doctor, nurse or other fields, to various enlisted specialties. The latter range from flight combat operations such as loadmaster, to working in a dining facility to ensure that Airmen are properly fed. There are additional occupational fields such as computer specialties, mechanic specialties, enlisted aircrew, communication systems, cyberspace operations, avionics technicians, medical specialties, civil engineering, public affairs, hospitality, law, drug counseling, mail operations, security forces, and search and rescue specialties.[117]

Beyond combat flight crew personnel, other combat USAF AFSCs are Special Tactics Officer [118], Combat Rescue Officer [119], Pararescue [120], Combat Control [121], Tactical Air Control Party [122], and Special Operations Weather Technician [123].

Nearly all enlisted career fields are "entry level", meaning that the USAF provides all training. Some enlistees are able to choose a particular field, or at least a field before actually joining, while others are assigned an AFSC at Basic Military Training (BMT). After BMT, new enlisted airmen attend a technical training school where they learn their particular AFSC. Second Air Force, a part of Air Education and Training Command, is responsible for nearly all enlisted technical training.[124][125]

Training programs vary in length; for example, 3M0X1 (Services) has 31 days of tech school training, while 3E8X1 (Explosive Ordnance Disposal) is one year of training with a preliminary school and a main school consisting of over ten separate divisions, sometimes taking students close to two years to complete. Officer technical training conducted by Second Air Force can also vary by AFSC, while flight training for aeronautically-rated officers conducted by AETC's Nineteenth Air Force can last well in excess of one year.[126]

USAF rank is divided between enlisted airmen, non-commissioned officers, and commissioned officers, and ranges from the enlisted Airman Basic (E-1) to the commissioned officer rank of General (O-10), however in times of war officers may be appointed to the higher grade of General of the Air Force. Enlisted promotions are granted based on a combination of test scores, years of experience, and selection board approval while officer promotions are based on time-in-grade and a promotion selection board. Promotions among enlisted personnel and non-commissioned officers are generally designated by increasing numbers of insignia chevrons.[127] Commissioned officer rank is designated by bars, oak leaves, a silver eagle, and anywhere from one to five stars.[128] General of the Air Force Henry "Hap" Arnold is the only individual in the history of the US Air Force to attain the rank of five-star general.[129]

As of 30 June 2017, 70% of the Air Force is White, 15% Black and 4.8% Asian. The average age is 35 and 21% of its members are female.[130]

Commissioned officers

The commissioned officer ranks of the USAF are divided into three categories: company grade officers, field grade officers, and general officers. Company grade officers are those officers in pay grades O-1 to O-3, while field grade officers are those in pay grades O-4 to O-6, and general officers are those in pay grades of O-7 and above.

Air Force officer promotions are governed by the Defense Officer Personnel Management Act of 1980 and its companion Reserve Officer Personnel Management Act (ROPMA) for officers in the Air Force Reserve and the Air National Guard. DOPMA also establishes limits on the number of officers that can serve at any given time in the Air Force. Currently, promotion from second lieutenant to first lieutenant is virtually guaranteed after two years of satisfactory service. The promotion from first lieutenant to captain is competitive after successfully completing another two years of service, with a selection rate varying between 99% and 100%. Promotion to major through major general is through a formal selection board process, while promotions to lieutenant general and general are contingent upon nomination to specific general officer positions and subject to U.S. Senate approval.

During the board process, an officer's record is reviewed by a selection board at the Air Force Personnel Center at Randolph Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas. At the 10 to 11-year mark, captains will take part in a selection board to major. If not selected, they will meet a follow-on board to determine if they will be allowed to remain in the Air Force. Promotion from major to lieutenant colonel is similar and occurs approximately between the fourteen year and the fifteen year mark, where a certain percentage of majors will be in zone (i.e., "on time") or above zone (i.e., "late") for promotion to lieutenant colonel. This process will repeat at the 18-year mark to the 21-year mark for promotion to full colonel.

The Air Force has the largest ratio of general officers to total strength of all of the U.S. Armed Forces and this ratio has continued to increase even as the force has shrunk from its Cold War highs.[131]

Warrant officers

Although provision is made in Title 10 of the United States Code for the Secretary of the Air Force to appoint warrant officers, the Air Force does not currently use warrant officer grades, and, along with the Space Force, are the only U.S. Armed Services not to do so. The Air Force inherited warrant officer ranks from the Army at its inception in 1947. The Air Force stopped appointing warrant officers in 1959,[133] the same year the first promotions were made to the new top enlisted grade, Chief Master Sergeant. Most of the existing Air Force warrant officers entered the commissioned officer ranks during the 1960s, but small numbers continued to exist in the warrant officer grades for the next 21 years.

The last active duty Air Force warrant officer, CWO4 James H. Long, retired in 1980 and the last Air Force Reserve warrant officer, CWO4 Bob Barrow, retired in 1992.[134] Upon his retirement, he was honorarily promoted to CWO5, the only person in the Air Force ever to hold this grade.[133] Since Barrow's retirement, the Air Force warrant officer ranks, while still authorized by law, are not used.

Enlisted airmen

Enlisted airmen have pay grades from E-1 (entry level) to E-9 (senior enlisted).[135] While all USAF personnel, enlisted and officer, are referred to as airmen, in the same manner that all Army personnel, enlisted and officer, are referred to as soldiers, the term also refers to the pay grades of E-1 through E-4, which are below the level of non-commissioned officers (NCOs). Above the pay grade of E-4 (i.e., pay grades E-5 through E-9) all ranks fall into the category of NCO and are further subdivided into "NCOs" (pay grades E-5 and E-6) and "senior NCOs" (pay grades E-7 through E-9); the term "junior NCO" is sometimes used to refer to staff sergeants and technical sergeants (pay grades E-5 and E-6).[136]

The USAF is the only branch of the U.S. military where NCO status is achieved when an enlisted person reaches the pay grade of E-5. In all other branches, NCO status is generally achieved at the pay grade of E-4 (e.g., a corporal in the Army[lower-alpha 4] and Marine Corps, Petty Officer Third Class in the Navy and Coast Guard). The Air Force mirrored the Army from 1976 to 1991 with an E-4 being either a senior airman wearing three stripes without a star or a sergeant (referred to as "buck sergeant"), which was noted by the presence of the central star and considered an NCO. Despite not being an NCO, a senior airman who has completed Airman Leadership School can be a supervisor according to the AFI 36–2618.[137]

| US DoD pay grade | Special | E-9 | E-8 | E-7 | E-6 | E-5 | E-4 | E-3 | E-2 | E-1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NATO code | OR-9 | OR-8 | OR-7 | OR-6 | OR-5 | OR-4 | OR-3 | OR-2 | OR-1 | |||||||

| Insignia | No insignia | |||||||||||||||

| Title | Senior Enlisted Advisor to the Chairman | Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force | Senior Enlisted Advisor to the Chief of the National Guard Bureau | Command chief master sergeant | Chief master sergeant[lower-alpha 5] | Senior master sergeant[lower-alpha 5] | Master sergeant[lower-alpha 5] | Technical sergeant | Staff sergeant | Senior airman | Airman first class | Airman | Airman basic | |||

| Abbreviation | SEAC | CMSAF | SEANGB | CCC/CCM | CMSgt | SMSgt | MSgt | TSgt | SSgt | SrA | A1C | Amn | AB | |||

Uniforms

The first USAF dress uniform, in 1947, was dubbed and patented "Uxbridge blue" after "Uxbridge 1683 blue", developed at the former Bachman-Uxbridge Worsted Company.[139] The current service dress uniform, which was adopted in 1994, consists of a three-button coat with decorative pockets, matching trousers, and either a service cap or flight cap, all in Shade 1620, "Air Force blue" (a darker purplish-blue).[140] This is worn with a light blue shirt (shade 1550) and shade 1620 herringbone patterned necktie. Silver "U.S." pins are worn on the collar of the coat, with a surrounding silver ring for enlisted airmen. Enlisted airmen wear sleeve rank on both the jacket and shirt, while officers wear metal rank insignia pinned onto the epaulet loops on the coat, and Air Force blue slide-on epaulet loops on the shirt. USAF personnel assigned to base honor guard duties wear, for certain occasions, a modified version of the standard service dress uniform that includes silver trim on the sleeves and trousers, with the addition of a ceremonial belt (if necessary), service cap with silver trim and Hap Arnold Device (instead of the seal of the United States worn on the regular cap), and a silver aiguillette placed on the left shoulder seam and all devices and accoutrements.

The Airman Combat Uniform (ACU) in the Operational Camouflage Pattern (OCP) replaced the previous Airman Battle Uniform (ABU) on 1 October 2018.[141][142]

Awards and badges

In addition to basic uniform clothing, various badges are used by the USAF to indicate a billet assignment or qualification-level for a given assignment. Badges can also be used as merit-based or service-based awards. Over time, various badges have been discontinued and are no longer distributed.

Training

All enlisted Airmen attend Basic Military Training (BMT) at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas for 7+1⁄2 weeks.[143] Individuals who have prior service of over 24 months of active duty in the other service branches who seek to enlist in the Air Force must go through a 10-day Air Force familiarization course rather than enlisted BMT, however prior service opportunities are severely limited.[144][145]

Officers may be commissioned upon graduation from the United States Air Force Academy, upon graduation from another college or university through the Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps (AFROTC) program, or through the Air Force Officer Training School (OTS). OTS, located at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama since 1993, in turn encompasses two separate commissioning programs: Basic Officer Training (BOT), which is for officer candidates for the Regular Air Force and the Air Force Reserve; and the Academy of Military Science (AMS), which is for officer candidates of the Air National Guard.

The Air Force also provides Commissioned Officer Training (COT) for officers of all three components who are direct-commissioned into medicine, law, religion, biological sciences, or healthcare administration. COT is fully integrated into the OTS program and today encompasses extensive coursework as well as field exercises in leadership, confidence, fitness, and deployed-environment operations.

Air Force Fitness Test

The US Air Force Fitness Test (AFFT) is designed to test the abdominal circumference, muscular strength/endurance and cardiovascular respiratory fitness of airmen in the USAF. As part of the Fit to Fight program, the USAF adopted a more stringent physical fitness assessment; the new fitness program was put into effect on 1 June 2010. The annual ergo-cycle test which the USAF had used for several years had been replaced in 2004. In the AFFT, Airmen are given a score based on performance consisting of four components: waist circumference, the sit-up, the push-up, and a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) run. Airmen can potentially earn a score of 100, with the run counting as 60%, waist circumference as 20%, and both strength tests counting as 10% each. A passing score is 75 points. Effective 1 July 2010, the AFFT is administered by the base Fitness Assessment Cell (FAC), and is required twice a year. Personnel earning a score over 90% may test once a year. Additionally, only meeting the minimum standards on each one of these tests will not get you a passing score of 75%, and failing any one component will result in a failure for the entire test.[146]

Aircraft inventory

The U.S. Air Force has a total force of 5,217 aircraft as of June 2021. Of these, 4,131 are in active service.[147] Until 1962, the Army and Air Force maintained one system of aircraft naming, while the U.S. Navy maintained a separate system. In 1962, these were unified into a single system heavily reflecting the Army and Air Force method. For more complete information on the workings of this system, refer to United States military aircraft designation systems. The various aircraft of the Air Force include:

A – Attack

The attack aircraft[148] of the USAF are designed to attack targets on the ground and are often deployed as close air support for, and in proximity to, U.S. ground forces. The proximity to friendly forces require precision strikes from these aircraft that are not always possible with bomber aircraft. Their role is tactical rather than strategic, operating at the front of the battle rather than against targets deeper in the enemy's rear. Current USAF attack aircraft are operated by Air Combat Command, Pacific Air Forces, and Air Force Special Operations Command. On 1 August 2022, USSOCOM selected the Air Tractor-L3Harris AT-802U Sky Warden as a result of the Armed Overwatch program, awarding an indefinite quantity contract (IDIQ) to deliver as many as 75 aircraft.[149]

B – Bomber

US Air Force bombers are strategic weapons, primarily used for long range strike missions with either conventional or nuclear ordnance. Traditionally used for attacking strategic targets, today many bombers are also used in the tactical mission, such as providing close air support for ground forces and tactical interdiction missions.[153] All Air Force bombers are under Global Strike Command.[154]

The service's B-2A aircraft entered service in the 1990s, its B-1B aircraft in the 1980s and its current B-52H aircraft in the early 1960s. The B-52 Stratofortress airframe design is over 60 years old and the B-52H aircraft currently in the active inventory were all built between 1960 and 1962. The B-52H is scheduled to remain in service for another 30 years, which would keep the airframe in service for nearly 90 years, an unprecedented length of service for any aircraft. The B-21 is projected to replace the B-52 and parts of the B-1B force by the mid-2020s.[155]

C – Transport

Transport aircraft are typically used to deliver troops, weapons and other military equipment by a variety of methods to any area of military operations around the world, usually outside of the commercial flight routes in uncontrolled airspace. The workhorses of the USAF airlift forces are the C-130 Hercules, C-17 Globemaster III, and C-5 Galaxy. The CV-22 is used by the Air Force for special operations. It conducts long-range, special operations missions, and is equipped with extra fuel tanks and terrain-following radar. Some aircraft serve specialized transportation roles such as executive or embassy support (C-12), Antarctic support (LC-130H), and AFSOC support (C-27J and C-146A). Although most of the US Air Force's cargo aircraft were specially designed with the Air Force in mind, some aircraft such as the C-12 Huron (Beechcraft Super King Air) and C-146 (Dornier 328) are militarized conversions of existing civilian aircraft. Transport aircraft are operated by Air Mobility Command, Air Force Special Operations Command, and United States Air Forces in Europe – Air Forces Africa.

- C-5M Galaxy[160][161]

- C-12C, C-12D, C-12F and C-12J Huron[162]

- C-17A Globemaster III[163][164]

- C-130H, LC-130H, and WC-130H Hercules

- C-130J and C-130J-30 Super Hercules

- C-135 Stratolifter

- C-145A Skytruck

- C-146A Wolfhound

- CV-22B Osprey

E – Special Electronic

The purpose of electronic warfare is to deny the opponent an advantage in the EMS and ensure friendly, unimpeded access to the EM spectrum portion of the information environment. Electronic warfare aircraft are used to keep airspaces friendly, and send critical information to anyone who needs it. They are often called "the eye in the sky". The roles of the aircraft vary greatly among the different variants to include electronic warfare and jamming (EC-130H), psychological operations and communications (EC-130J), airborne early warning and control (E-3), airborne command post (E-4B), ground targeting radar (E-8C), range control (E-9A), and communications relay (E-11A, EQ-4B).

- E-3B, E-3C and E-3G Sentry

- E-4B "Nightwatch"

- E-8C JSTARS

- E-9A Widget

- E-11A

- EC-130H Compass Call

- EC-130J Commando Solo

- EQ-4B Global Hawk

F – Fighter

The fighter aircraft of the USAF are small, fast, and maneuverable military aircraft primarily used for air-to-air combat. Many of these fighters have secondary ground-attack capabilities, and some are dual-roled as fighter-bombers (e.g., the F-16 Fighting Falcon); the term "fighter" is also sometimes used colloquially for dedicated ground-attack aircraft, such as the F-117 Nighthawk. Other missions include interception of bombers and other fighters, reconnaissance, and patrol. The F-16 is currently used by the USAF Air Demonstration squadron, the Thunderbirds, while a small number of both man-rated and non-man-rated F-4 Phantom II are retained as QF-4 aircraft for use as full-scale aerial targets (FSATs) or as part of the USAF Heritage Flight program. These extant QF-4 aircraft are being replaced in the FSAT role by early model F-16 aircraft converted to QF-16 configuration. The USAF had 2,025 fighters in service as of September 2012.[165]

- F-15C and F-15D Eagle

- F-15E Strike Eagle

- F-15EX Eagle II[166]

- F-16C, F-16D, and F-16V Fighting Falcon

- F-22A Raptor

- F-35A Lightning II

H – Search and rescue

These aircraft are used for search and rescue and combat search and rescue on land or sea. The HC-130N/P aircraft are being replaced by newer HC-130J models. HH-60W are replacement aircraft for "G" models that have been lost in combat operations or accidents. New HH-60W helicopters are under development to replace both the "G" and "W" model Pave Hawks. The Air Force also has four HH-60U "Ghost Hawks", which are converted "M" variants. They are based out of Area 51.[167]

K – Tanker

The USAF's KC-135 and KC-10 aerial refueling aircraft are based on civilian jets. The USAF aircraft are equipped primarily for providing the fuel via a tail-mounted refueling boom, and can be equipped with "probe and drogue" refueling systems. Air-to-air refueling is extensively used in large-scale operations and also used in normal operations; fighters, bombers, and cargo aircraft rely heavily on the lesser-known "tanker" aircraft. This makes these aircraft an essential part of the Air Force's global mobility and the U.S. force projection. The KC-46A Pegasus began to be delivered to USAF units starting in 2019.

M – Multi-mission

Specialized multi-mission aircraft provide support for global special operations missions. These aircraft conduct infiltration, exfiltration, resupply, and refueling for SOF teams from improvised or otherwise short runways. The MC-130J is currently being fielded to replace "H" and "P" models used by U.S. Special Operations Command. The MC-12W is used in the "intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance" (ISR) role.

Initial generations of RPAs were primarily surveillance aircraft, but some were fitted with weaponry (such as the MQ-1 Predator, which used AGM-114 Hellfire air-to-ground missiles). An armed RPA is known as an "unmanned combat aerial vehicle" (UCAV).

O – Observation

These aircraft are modified to observe (through visual or other means) and report tactical information concerning composition and disposition of forces. The OC-135 is specifically designed to support the Treaty on Open Skies by observing bases and operations of party members under the 2002-signed treaty.

R – Reconnaissance

The reconnaissance aircraft of the USAF are used for monitoring enemy activity, originally carrying no armament. Although the U-2 is designated as a "utility" aircraft, it is a reconnaissance platform. The roles of the aircraft vary greatly among the different variants to include general monitoring, ballistic missile monitoring (RC-135S), electronic intelligence gathering (RC-135U), signal intelligence gathering (RC-135V/W), and high altitude surveillance (U-2)

Several unmanned remotely controlled reconnaissance aircraft (RPAs), have been developed and deployed. Recently, the RPAs have been seen to offer the possibility of cheaper, more capable fighting machines that can be used without risk to aircrews.

- RC-135S Cobra Ball

- RC-135U Combat Sent

- RC-135V and RC-135W Rivet Joint

- RQ-4B Global Hawk

- RQ-11 Raven

- RQ-170 Sentinel

- U-2S "Dragon Lady"

T – Trainer

The Air Force's trainer aircraft are used to train pilots, combat systems officers, and other aircrew in their duties.

- T-1A Jayhawk

- T-6A Texan II

- T-38A, (A)T-38B and T-38C Talon

- T-41D Mescalero

- T-51A

- T-53A Kadet II

- TC-135W

- TE-8A JSTARS

- TH-1H Iroquois

- TU-2S Dragon Lady

TG – Trainer gliders

Several gliders are used by the USAF, primarily used for cadet flying training at the U.S. Air Force Academy.

U – Utility

Utility aircraft are used basically for what they are needed for at the time. For example, a Huey may be used to transport personnel around a large base or launch site, while it can also be used for evacuation. These aircraft are all around use aircraft.

V – VIP staff transport

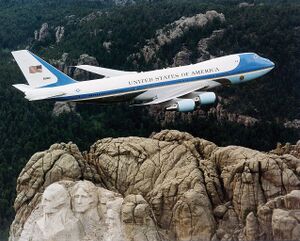

These aircraft are used for the transportation of Very Important Persons (VIPs). Notable people include the president, vice president, cabinet secretaries, government officials (e.g., senators and representatives), the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and other key personnel.

- VC-25A (two used as Air Force One)

- C20B Gulfstream III, C20H Gulfstream IV

- C-21A Learjet

- C-32A and C-32B (used as Air Force Two)

- C-37A Gulfstream V and C-37B Gulfstream G550

- C-40B and C-40C

W – Weather reconnaissance

These aircraft are used to study meteorological events such as hurricanes and typhoons.

Undesignated foreign aircraft

See also

- Air & Space Forces Association

- Air Force Combat Ammunition Center

- Air Force Knowledge Now

- Airman's Creed

- Civil Air Patrol

- Company Grade Officers' Council

- Department of the Air Force Police

- Future military aircraft of the United States

- List of military aircraft of the United States

- List of military aircraft of the United States (1909–1919)

- List of undesignated military aircraft of the United States

- List of United States Air Force installations

- List of United States Airmen

- List of U.S. Air Force acronyms and expressions

- National Museum of the United States Air Force

- Structure of the United States Air Force

- United States Air Force Band

- United States Air Force Chaplain Corps

- United States Air Force Combat Control Team

- United States Air Force Medical Service

- United States Air Force Thunderbirds

- Women in the United States Air Force

Notes

- ↑ After the United States Space Force, founded in 2019

- ↑ Reserved for wartime use only.

- ↑ No periods are used in actual grade abbreviation, only in press releases to conform with AP standards.[132]

- ↑ However, the Army has dual ranks at the E-4 paygrade with Specialists not considered NCOs. Since the 1980s, the Army corporal rank has come to be awarded infrequently and is rarely found in modern units.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Air Force first sergeants are considered temporary and lateral ranks and are senior to their non-diamond counterparts. First sergeants revert to their permanent rank within their paygrade upon leaving assignment.[138]

References

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ [Strength Changes (Last 12 Months)

- ↑ [1], DMDC official website, accessed 14 September 2023

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ 22.00 22.01 22.02 22.03 22.04 22.05 22.06 22.07 22.08 22.09 22.10 22.11 22.12 22.13 22.14 22.15 22.16 22.17 22.18 22.19 22.20 22.21 22.22 22.23 22.24 22.25 Air Force Basic Doctrine, Organization, and Command Archived 18 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine (PDF), 14 October 2011

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Robert Pitta, Gordon Rottman, Jeff Fannell (1993). US Army Air Force (1) Archived 28 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Osprey Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 1-85532-295-1

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ "The Air Force Fact Sheet" Archived 8 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. U.S. Air Force. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ National Security Act of 1947. U.S. Intelligence Community, October 2004. Retrieved 14 April 2006.

- ↑ U.S. Department of State. National Security Act of 1947 Archived 27 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Bennett, John T. "Panetta Selects Trusted Hand for New Air Force Chief." Archived 29 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine U.S. News & World Report, 14 May 2012.

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Needed: 200 New Aircraft a Year Archived 20 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Air Force Magazine, October 2008.

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value). 1991: 510,000; 2007: 328,600

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ "Washington watch" Archived 20 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, AIR FORCE Magazine, July 2008, Vol. 91 No. 7, pp. 8.

- ↑ Chavanne, Bettina H. "USAF Creates Global Strike Command" Archived 11 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Aviation Week, 24 October 2008.

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ The primary source for the humanitarian operations of the USAF is the United States Air Force Supervisory Examination Study Guide (2005)

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Schwellenbach, Nick. "Brass Creep and the Pentagon: Air Force Leads the Way As Top Offender." Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine POGO, 25 April 2011.

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ 133.0 133.1 Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).